In September 2019, at the Yorkshire Fossil Festival, I organized a Geology Hull event called 'Jobs That Rock', which brought geologists and would-be geologists together to discuss careers in the Earth sciences:

Jobs that Rock 2019 from University of Hull NYPH on Vimeo.

The world needs more Earth scientists. As a Lecturer in Geology and Director of Admissions for the Department of Geography, Geology and Environment at the University of Hull, I am obliged to say this, but it's true. Virtually every one of the big challenges facing us in the 21st Century - climate change, energy, sustainability, geohazards, infrastructure, resources - requires people with a good understanding of geology.

Over the last few weeks, I've been discussing this with my undergraduate tutees, as I try to advise them on what careers might be of interest, and what they need to do to give themselves a chance of success. However, I've never really analysed my own geology career.

It now being 20 years since I began my PhD, I am in retrospective mode. I thought it might be vaguely useful to review what I've done, how I got there, and what I've learned.

1) Well, firstly, it's probably wise to get a degree in a geological subject. I did Geology with Physical Geography at the University of Liverpool and had a marvellous time. It certainly helped to be given a tutor as great as the man, the legend Jim Marshall. I did quite well in my first year (probably because I'd done A-Level Geology), quite poorly in my second year (distractions and poor motivation), and then very well in my final year, when I found options and projects that I really enjoyed.

2) After that, if you're rather unsure what to do next, you might do what I did and go back home. That first post-graduate summer, I worked in my Dad's office, until a Professor of Sedimentology phoned me up out of the blue and asked if I wanted to be a research assistant. This might not be something you've even thought was possible (I'm not sure I did), but keeping in touch with your tutors and lecturers is certainly a good idea. I ended up doing a six-month position studying the Carboniferous turbidites of western Ireland, and one of my coursemates also got employed, as he had a driving licence and I didn't.

3) When that job runs its course and you've decided you quite like research, you might consider applying for PhDs. I didn't have much of a system. I just applied for projects that interested me, mostly palaeontological. I got interviews at four universities, and was offered two projects. As only one of them was fully funded, I chose that one. With hindsight, I probably wouldn't recommend choosing a niche palaeontological topic. I love the Much Wenlock Limestone Formation, and am very proud of the research I published with my excellent PhD supervisors, Alan Thomas and Paul Smith. However, the academic world is very competitive. Having achieved my doctorate I soon realised there were plenty of other folks out there with more useful expertise than me and my extensive knowledge of systematic palaeontology and Silurian starfish.

4) Still, I was now a doctor of rock, which must count for something? After retreating to the desert for two months, I returned to the parental home with no clear plan (you'll notice a theme here). I joined a temping agency and got a job in a university finance office, an unexpected transferable skill of my PhD being that I could now type at 55 words per minute. I temped for a year, and worked with some lovely people, but I can't say I acquired any further transferable skills as a result. The two primary learning outcomes were 1) I needed to get back into something geological, and 2) living at home in your late 20s is good for neither you nor your parents.

5) Having maintained my links with the department I did my PhD in, a couple of short-term possibilities arose there. This again emphasizes the value of staying in touch with people. However, neither job was going to be well-paid, or full-time, and as I had no savings to speak of, I couldn't see how I could make a living. I was then very lucky that a geological friend who'd just bought his first house was looking for someone to live in his spare room at a very low rent, so I took a chance and crossed back from the East to West Midlands.

INTERMISSION

People fond of quoting blanditudes often say 'never go back' and 'learn how to say no'. My advice is 'sometimes go back, particularly if you've got nothing better on the table,' and 'say yes to everything that sounds interesting, particularly if you've got nothing better on the table.'

Within a year, I'd helped produce new marketing materials for the Lapworth Museum of Geology, edited a NATO volume on Urban Groundwater, and - more importantly - met my girlfriend*. It had definitely been worthwhile.

6) After a shoestring year wondering how and where I might get a longer-term, fuller-paid job that didn't involve accommodation-scrounging, my friend from the desert alerted me to a two-year postdoctoral position in her department in Aberdeen. I submitted an application and was eventually called up for a January interview. I gave a reasonable talk on my research interests, but it seemed the department was split between needing a palaeontologist and definitely not needing a palaeontologist. I heard nothing for many weeks, and assumed the latter faction had won. And then I got the letter offering me the job, and without too much hesitation, I accepted.

More than two years after finishing my PhD, I was actually a postdoc. What exciting times! OK, so the commute between my girlfriend's flat in south-west Birmingham and the university in north-east Scotland was going to be a challenge, but I'd got a proper job! I moved to Aberdeen in late April, to begin working in May, giving me plenty of time to kick off some new research, and get prepared for teaching in September.

But wait! How on Earth had I got this job? What relevant research and teaching skills did I really have? How could I be responsible for teaching and supervising undergraduate geologists? And how was I going to turn a two-year postdoc into a proper career? It was time for some impostor syndrome to kick in, a challenge that I've wrestled with ever since, and which I'll look at it in a bit more detail in part two...

Jobs that Rock 2019 from University of Hull NYPH on Vimeo.

The world needs more Earth scientists. As a Lecturer in Geology and Director of Admissions for the Department of Geography, Geology and Environment at the University of Hull, I am obliged to say this, but it's true. Virtually every one of the big challenges facing us in the 21st Century - climate change, energy, sustainability, geohazards, infrastructure, resources - requires people with a good understanding of geology.

Over the last few weeks, I've been discussing this with my undergraduate tutees, as I try to advise them on what careers might be of interest, and what they need to do to give themselves a chance of success. However, I've never really analysed my own geology career.

It now being 20 years since I began my PhD, I am in retrospective mode. I thought it might be vaguely useful to review what I've done, how I got there, and what I've learned.

WARNING: OLD CODGER ALERT

1) Well, firstly, it's probably wise to get a degree in a geological subject. I did Geology with Physical Geography at the University of Liverpool and had a marvellous time. It certainly helped to be given a tutor as great as the man, the legend Jim Marshall. I did quite well in my first year (probably because I'd done A-Level Geology), quite poorly in my second year (distractions and poor motivation), and then very well in my final year, when I found options and projects that I really enjoyed.

|

| A 20-year reunion on the steps of the Herdman Building. |

2) After that, if you're rather unsure what to do next, you might do what I did and go back home. That first post-graduate summer, I worked in my Dad's office, until a Professor of Sedimentology phoned me up out of the blue and asked if I wanted to be a research assistant. This might not be something you've even thought was possible (I'm not sure I did), but keeping in touch with your tutors and lecturers is certainly a good idea. I ended up doing a six-month position studying the Carboniferous turbidites of western Ireland, and one of my coursemates also got employed, as he had a driving licence and I didn't.

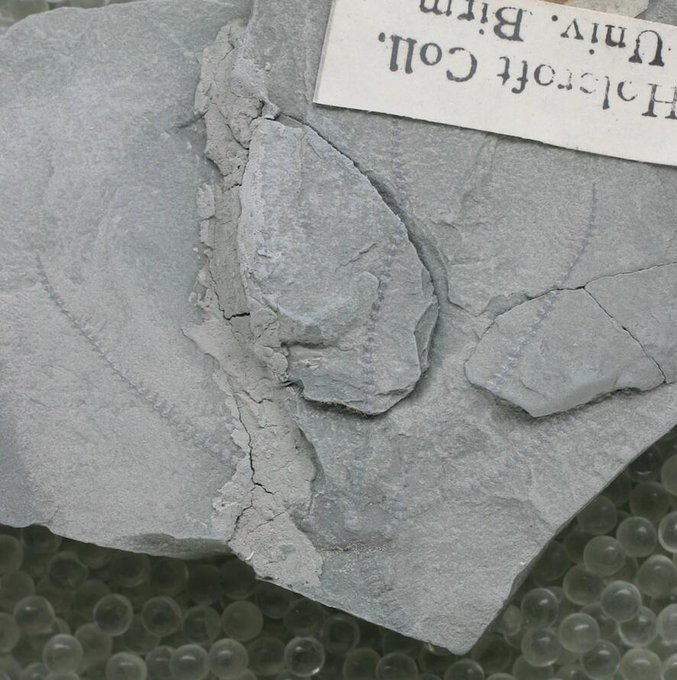

3) When that job runs its course and you've decided you quite like research, you might consider applying for PhDs. I didn't have much of a system. I just applied for projects that interested me, mostly palaeontological. I got interviews at four universities, and was offered two projects. As only one of them was fully funded, I chose that one. With hindsight, I probably wouldn't recommend choosing a niche palaeontological topic. I love the Much Wenlock Limestone Formation, and am very proud of the research I published with my excellent PhD supervisors, Alan Thomas and Paul Smith. However, the academic world is very competitive. Having achieved my doctorate I soon realised there were plenty of other folks out there with more useful expertise than me and my extensive knowledge of systematic palaeontology and Silurian starfish.

|

| The Silurian sea lily, Calyptocymba, from the Much Wenlock Limestone Formation of Dudley (image copyright: Liam Herringshaw). |

4) Still, I was now a doctor of rock, which must count for something? After retreating to the desert for two months, I returned to the parental home with no clear plan (you'll notice a theme here). I joined a temping agency and got a job in a university finance office, an unexpected transferable skill of my PhD being that I could now type at 55 words per minute. I temped for a year, and worked with some lovely people, but I can't say I acquired any further transferable skills as a result. The two primary learning outcomes were 1) I needed to get back into something geological, and 2) living at home in your late 20s is good for neither you nor your parents.

5) Having maintained my links with the department I did my PhD in, a couple of short-term possibilities arose there. This again emphasizes the value of staying in touch with people. However, neither job was going to be well-paid, or full-time, and as I had no savings to speak of, I couldn't see how I could make a living. I was then very lucky that a geological friend who'd just bought his first house was looking for someone to live in his spare room at a very low rent, so I took a chance and crossed back from the East to West Midlands.

INTERMISSION

People fond of quoting blanditudes often say 'never go back' and 'learn how to say no'. My advice is 'sometimes go back, particularly if you've got nothing better on the table,' and 'say yes to everything that sounds interesting, particularly if you've got nothing better on the table.'

Within a year, I'd helped produce new marketing materials for the Lapworth Museum of Geology, edited a NATO volume on Urban Groundwater, and - more importantly - met my girlfriend*. It had definitely been worthwhile.

*The fact that I felt I'd rather outstayed my landlord's kind welcome,

and that she had just bought her first house, was pure coincidence.

Oh, oh, oh, I was, I was the bed and breakfast man.

6) After a shoestring year wondering how and where I might get a longer-term, fuller-paid job that didn't involve accommodation-scrounging, my friend from the desert alerted me to a two-year postdoctoral position in her department in Aberdeen. I submitted an application and was eventually called up for a January interview. I gave a reasonable talk on my research interests, but it seemed the department was split between needing a palaeontologist and definitely not needing a palaeontologist. I heard nothing for many weeks, and assumed the latter faction had won. And then I got the letter offering me the job, and without too much hesitation, I accepted.

More than two years after finishing my PhD, I was actually a postdoc. What exciting times! OK, so the commute between my girlfriend's flat in south-west Birmingham and the university in north-east Scotland was going to be a challenge, but I'd got a proper job! I moved to Aberdeen in late April, to begin working in May, giving me plenty of time to kick off some new research, and get prepared for teaching in September.

|

| A very old phone photo of His Majesty's Theatre and Union Terrace Gardens, Aberdeen. |

But wait! How on Earth had I got this job? What relevant research and teaching skills did I really have? How could I be responsible for teaching and supervising undergraduate geologists? And how was I going to turn a two-year postdoc into a proper career? It was time for some impostor syndrome to kick in, a challenge that I've wrestled with ever since, and which I'll look at it in a bit more detail in part two...

Comments