Genealogy can become quite addictive. Most of us want to know where we came from, and the huge resources

now available online make it quite easy to begin building up a record

of our ancestors.

Records alone are dull though; a

simple list of names and dates is dry. If a family phylogeny is worth

its salt, the people need to come to life. It helps us better

understand the past, and perhaps ourselves. It might also reveal

some interesting stories.

Over the last few months, with lots of assistance from Hen, I've been

exploring my maternal lineage, a mostly West Yorkshire-based clan who

are still close, even though they left that riding many moons ago. Of

particular interest is their homestead of Clayton, a village a few

miles west of Bradford, where most of my grand-maternal relatives

lived.

|

| Clayton Baptist Church (from Wikimedia Commons). |

Until this year, I'd never actually

been there, but I knew lots of the family names, and some of the

places. This whetted my appetite, and I soon became engrossed in the

process of fleshing the people out, and tracing their origins further

back.

Of particular interest were the Foulds. Their name had percolated through my childhood from Mum and Grandma's tales,

though the closest relatives with that name to me were my

great-great-grandparents, Edwin and Emma, both of whom were dead long before I was born.

Edwin intrigued me though, as he

shouldn't have been a Foulds. His father was George Briggs. It

transpired he was born before his parents married, so he took his

mother Susannah's maiden name. All his subsequent siblings were

Briggses.

That was a bit confusing, but not

unprecedented. What did pique my curiosity was Susannah and George's

marriage certificate, which stated that her father, Robert Foulds, was a

'delver', whilst George's was a 'gentleman'.

|

| The Delvers' Arms, Southowram, West Yorkshire (from Wikimedia Commons). |

At first glance, I understood 'delver' to be a ditch-digger, which suggested a somewhat Pygmalion-esque tale of rags to riches. I could almost imagine the tabloid headline: "Ditch-Digger's Daughter Delights Dapper Dandy".

I then found out that delver could also mean a quarryman. As a geologist, I was very pleased by the possibility, but I needed more facts. Was that interpretation correct? Where was the quarry? And what stone was it extracting?

I stumbled upon the marvellous Clayton History Group website, and when I typed 'Foulds' into its search engine there were two hits: one in the extracts from local newspapers, the other in a 'Then and Now' section of the local history.

I stumbled upon the marvellous Clayton History Group website, and when I typed 'Foulds' into its search engine there were two hits: one in the extracts from local newspapers, the other in a 'Then and Now' section of the local history.

And imagine my excitement when the first record said this:

"7th

JULY 1900 The largest ever fossil tree ever found. This interesting

relic of antiquity, which has been discovered at Fall Top Quarry,

Clayton, owned by Mr Robert Foulds, is now on view prior to removal.

A small charge is made for admission, of which a large proportion

will be donated to the Lord Mayors Fund."

A fabulous fossil tree, found by a

Foulds in Fall Top Quarry? Flippin' fantastic!

|

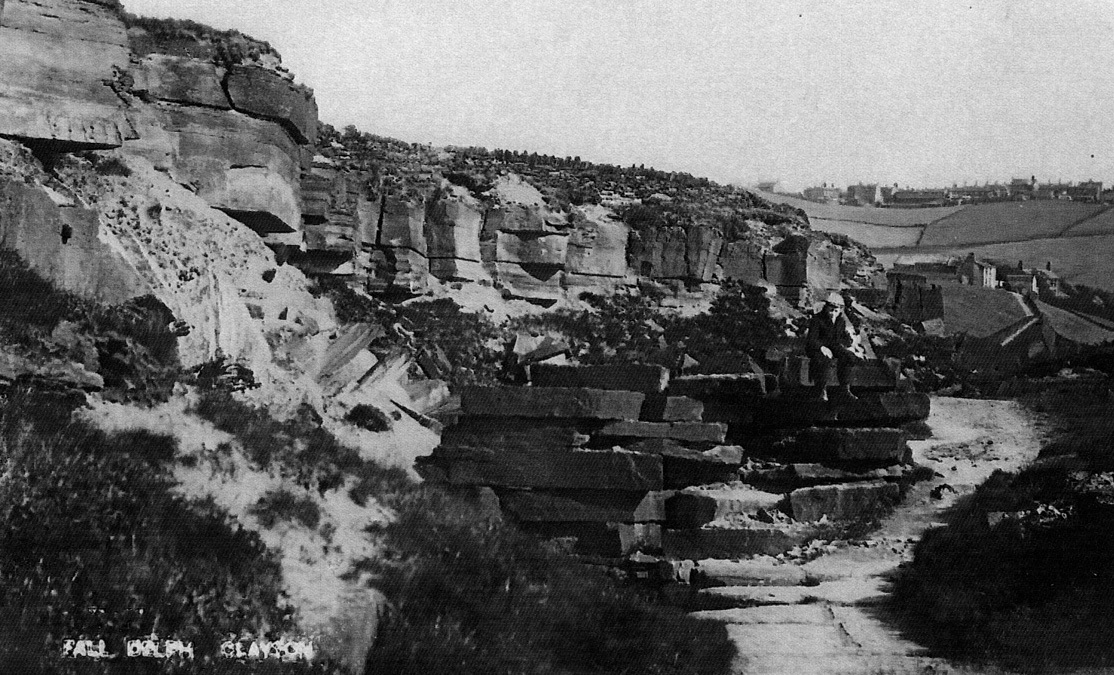

| Fall Top Quarry, Clayton, 1906 (from the Clayton History Group website) |

My academic scepticism is always there, though, so I tried not to get carried away. Pleasingly, the second page provided more details:

"The

Foulds family owned quarries at Fall Top, then later moved to Middle

Lane, with an office at 70 Clayton Lane. They employed about 30

people, mainly labourers, including several Irish labourers from

Bradford. They and other quarry owners were also quite large

employers of local labour, as is shown by the number of

quarry-workers in the registers of the Parish Church. Whilst

quarrying at Fall Top a fossil tree root several million years old

was found. This was a perfect specimen and was taken to Lister Park,

though Mr. Harry Foulds, grandson of the founder, still has a portion

of it in his garden."

|

| The fossil tree in Lister Park, Bradford (August 2005: Wikimedia Commons) |

My excitement was now getting out of hand, tempered only by one fear: that the fossil-finding Foulds was not my relative. There was no doubt that the Clayton delvers were quarrymen, as it was stated elsewhere that:

'The

stone was in great demand and all the delving was done by hand.'

The Huddersfield Geology Group explained that a delver was a specialized quarryman, one who identified which stone layers should be extracted. Were these the right quarrymen

though?

I went back into my family tree, and

found it contained two Robert Foulds. The delver – Susannah's

father, my great-great-great-great grandpa – was too old to be the man in question. He was born in 1800. The other, however, was his grandson, my first

cousin four times removed, and he was quite the right age.

Tracking him through the census

records, Robert junior followed exactly the career trajectory I

wanted him to. In 1881, aged 16, he was a quarryman. Ten years later he was a

flag facer, or stone dresser. By 1891 the 36 year-old Robert was the quarry owner.

Thanks to the records of the Northern Mine Research Society and the Peak District Mines Historical Society, I was then able to clarify that, between 1891 and 1905, he operated three quarries in Clayton, first at Broad Fold, then at Near Fold, and then at Fall Top. All were mining the Carboniferous sandstone of which so much of the West Riding's buildings are constructed (such as this rather magnificent one).

Thanks to the records of the Northern Mine Research Society and the Peak District Mines Historical Society, I was then able to clarify that, between 1891 and 1905, he operated three quarries in Clayton, first at Broad Fold, then at Near Fold, and then at Fall Top. All were mining the Carboniferous sandstone of which so much of the West Riding's buildings are constructed (such as this rather magnificent one).

|

| Yorkshire Grit: Westphalian sandstones in Clayton. |

These sands were laid down in huge

tropical river systems around 310 million years ago, in the earliest

phases of deposition of what would eventually become the Coal

Measures. Coal is made of compressed plants, and the biggest plants

of the time – tree-ferns – grew in well-drained sandy soils. As

such, every so often, Yorkshire quarrymen would encounter fossilized

examples of the root systems as they smashed their way through the

sandstones.

Clayton seems to have been a hotspot,

and the remarkable remains were a topic of great wonder. Astute, or

perhaps beneficent, quarry owners recognized this, and the fossils were

extracted for public display. In the late 19th

or early 20th centuries, most of Bradford's city parks - Lister, Horton, Bolton -

acquired a tree of their own, and you can still go and see them

today.

Sadly from my perspective, it seems the story

that the tree in Lister Park is Robert Foulds' is

incorrect. The records I've unearthed indicate that the park received its

fossil in 1889, more than a decade beforehand. In the year Foulds found his fossil, the Lister Park tree was already in place. As was the one in Horton Park:

|

| Fossil Stigmaria tree, Horton Park, Bradford (Photo (C) Liam Herringshaw) |

If that was disappointing, though, it was soon tempered, because there was one more photograph of Bradford fossil trees. This one:

|

| Clayton, Bradford, Stigmaria in situ (image from BGS Geoscenic) |

The picture featured in a report of the 1902 Belfast meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and was illustrating an excursion that took place two years earlier, when the BAAS met in Bradford. There's no mention of which Clayton quarry the scientists visited, but I refuse to accept that there were two giant Carboniferous coal trees found in the village that year.

Wherever it may now be, this is Robert Foulds' fossil.

This is my family tree.

Wherever it may now be, this is Robert Foulds' fossil.

This is my family tree.

Comments